Readers of my historical novel, Though An Army Come Against Us, often report encountering episodes that are simply too much for them to believe. They set the book down, shaking their heads, and saying to themselves, "Rick, you really went too far this time." Then they google the incident and discover that it is, instead, simply true.

I tell them that my imagination isn't all that good. I tell them that the history of this country can be so dark that I don't need any imagination to conjure up these horrors. And it surprises me because I have spent all my adult life looking into those corners. Some were astonished by the presence of gas chambers at the El Paso-Ciudad Juárez border crossing that was a model for Hitler's gas chambers. Some were surprised by the coal mine explosions I described in Dawson, New Mexico and Littleton, Alabama, or by the fact that seventy-two of the miners killed in the latter were convicts leased by the company from state and county prisons. One reader hadn't heard about the massacre of striking miners' families in Ludlow, Colorado. Another learned for the first time about the Tulsa Massacre that has been so present lately in popular culture.

But my imagination is really not that good, and even many of the minor details in my fiction are factually and historically correct. Unfortunately my notes are not all that great either, because I am not preparing them for academic publication. I have sources listed in multiple notes in Apple Notes on both my phone and laptop. I have highlighted passages in Kindle from ebooks I read. I have PDFs saved in a folder on my laptop. I have files sent to me from various archivists and librarians. And I have handwritten notes in steno pads and notebooks. Retracing my steps can be a colossal challenge, especially when the information was obscure and hard to find in the first place.

This morning I was writing a Facebook post about the experiences Black soldiers had with racist violence while they were in Europe during the First World War. There is an episode in Though An Army in which Rector Beauchamp, a Black Seminole soldier, is nearly lynched by white soldiers led by two white officers who are jealous that a French girl turns to him to rescue herself from them. But a year and a half after I published this, several years after I wrote those particular pages, and who-knows-how-long after I researched them, I couldn't remember why I thought there were lynchings in the American Expeditionary Force in 1918.

I googled those words and easily found references to the Red Summer of 1919 and to lynchings of returned veterans. It took me about 45 minutes to find a popular magazine article by Professor Chad Williams, and then a note in an article that cited a book he wrote titled Torchbearers of Freedom:African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. That was a familiar title, so I looked in my Kindle library. Success!

Instead of using the Kindle search function I simply scrolled through the passages I had highlighted and there it was. Some Black officers had aroused the envy of white officers over the attentions of some French women so the white men got two truckloads of white enlisted men and ordered them to lynch the Black officers. Moreover the incident had been reported by First Lieutenant Charles Hamilton Houston. Yes, that is the Charles Hamilton Houston. He had been an English professor at Howard before enlisting, but after his wartime experiences he attended Harvard Law School. He returned to Howard as a law professor and trained the entire generation of NAACP Legal Defense Fund attorneys that included Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.

When I read this again this morning I wondered briefly why I left C.H. Houston out of my novel. But I remembered that I still have too many characters. Something like his part in the story and that of an unnamed captain are taken in Though An Army by the historical figure Osceola McKaine who was a captain in France, served in the infantry before the war in the Philippines and Mexico, and was a figure in the movement for Black rights after both the first and second World Wars. In Houston's story, retold by Professor Williams in Torchbearers, the two French women are described as "sporting girls." I chose to remove that characterization and turn them into one young teen who is both confused by the attention of the white officers and in danger of being raped by them. The whole thing reminded me of how it is sometimes when people ask me the specific source of some of these stories and I can't really remember.

1st Lieutenant Houston

It also made me wonder about how Professor Houston had told this story. That was another hour-long rabbit hole. The footnote in Torchbearers cited a series in the Pittsburgh Courier that Houston wrote in 1940 as the U.S. was about to get into another World War. I immediately went to the Library of Congress website because they have digitized huge numbers of newspapers. Nope. After hunting around for who might in fact have it I discovered a Proquest database, but my university alumni privileges don't extend to that. A recent laptop update erased my New York Public Library password, but I found it in one of those steno pads I have piled up and - Yes! - a few minutes later, having scanned through thirteen pages of the Courier on the listed date, I found episode ten of Houston's article, which contained more details. (The story also had to be continued on page 13 of the next issue, but that didn't take as long to get to.)

Then I started wondering again why I left Professor Houston out of my novel, especially since I had an entire short chapter take place in the "Colored" Officers Training Camp at Fort Des Moines, Iowa. And that led me to think about the contemporary souvenir book about that camp that I remembered reading online. Another hour. Not in Google Books. Not in the Library of Congress. Not in Iowa Pathways, although they did have PDFs of newspaper ads for the book. I finally found a link to an "online books page" at University of Pennsylvania Library which led me to a HathiTrust page which was where I am pretty sure I originally read this book however long ago.

Do I want to do this again? Not for these particular sources. I started a document with the links and basic information and I'm calling it Annotations. I don't want to track everything down, but I think that every time I do, I should save the links in that document. My memory only promises to get worse with time.

|

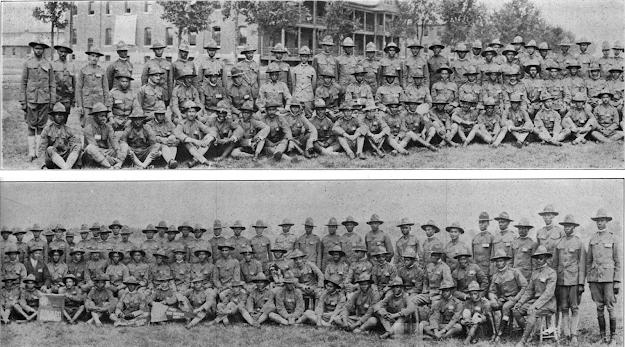

| This is a split group photo from that souvenir Fort Des Moines book. It shows all the Howard University grads at the training camp, the largest group of alums of any college. |